Crowdy McCrowdface problems generate Boaty McBoatface solutions.

George Shewchuk

( or, How the wisdom of the crowd capsized a boat naming challenge. )

(This was an article that I originally wrote as my entry to a HeroX.com blog writing challenge, Sept. 2020. It has since been edited to better reflect my perspective on using "crowdsourcing" as a tool for ideation)

In March 2016, 124,010 people chose Boaty McBoatface as their favourite entry for the Name Our Ship Contest launched by The Natural Environment Research Council, the UK's leading public funder of environmental science. The Council inadvertently tapped into a wise-cracking crowd! So, what happened?

Is Collaborative genius at work or just a bunch of jokesters having a bit of fun?

Getting buy-in from the public for serious scientific endeavours

The wisdom of the crowd gets lost in the hilarity of it all.

What motivates the crowd to participate?

Is there a better way to get the public on board with the launch of a very expensive ($287 million!) brand new research vessel to roam the polar seas than inviting them to participate in a name-the-boat contest? A naming contest is fun. It's easy. Just submit a name and vote for your favourite, no muss or fuss. You could spend as much time investigating the history of the Research Council and their various endeavours to come up with the perfect name. Or you could submit: "Its Bloody Cold Here," "What Iceberg?", "Captain Haddock," "Big Shipinnit," or how about, "Science!!!" Funny stuff that didn't require a lot of thought.

A naming challenge offers a rather binary solution space. To put it another way, determining the “success” of the solution without any objective criteria, apart from appropriateness, does not give the crowd much cognitive load to carry (hence the humorous entries). A true challenge is only as good as the rubric by which the solutions can be measured. This is not to say that crowdsourcing a name for any artifact is a bad idea, but just be prepared to wade through many bad ideas.

The Natural Environment Research Council’s intent was noble. To get people interested in the kind of scientific research that they do. But Scientific research is painstakingly slow, deliberate and esoteric by nature. It seemed appropriate at the time, one might imagine, that this is a great way to get the public on board: launch a non-technical, friendly naming contest. But it’s not exactly crowdsourcing citizen science! What could go wrong?

But who would have ever thought there would be well over 100,000 people giving the thumbs up to one of the silliest entries? Was this crowd not somehow automatically curated because the Natural Environment Research Council issued the challenge? I’m sure the government agency types thought they would be reaching out to the more science-minded crowd.

Wisdom of the Crowd or just Bad Ideas?

“I voted for Boaty McBoatface, and I did it for fun, laughter and anti-pomposity,”

said one participant.

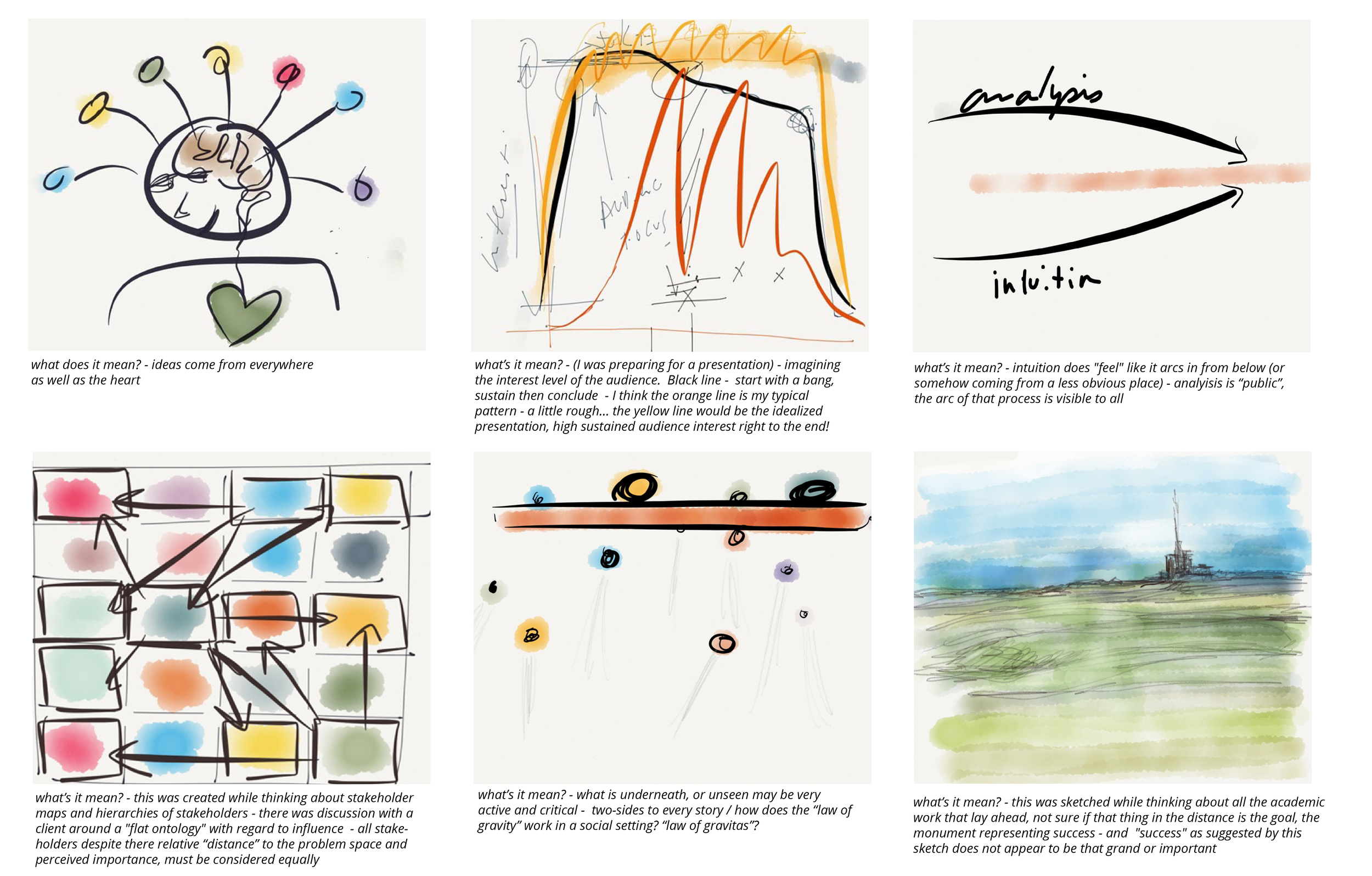

Was the wisdom of the crowd really at work here? Blue sky ideation was undoubtedly present in its most creative form. The most voted-for entry is indeed a funny name in a sophomoric way and identifies a catchy naming formula that spawned a litany of Namey McNameface names in many other categories ever since Boaty McBoatface hit the news.

So, whatever happened to the wisdom of the crowd? “Who cares what the sodding boat is called?” laments another contest observer. This is a telling comment. Who DOES care? And what does it matter what some boat is called? Winning this type of contest or challenge is akin to playing the lottery. There were no tools offered to help contestants strategize a process to get to the perfect name. There were no tools because there was nothing to offer other than announcing that a new research vessel was about to leave the dry dock.

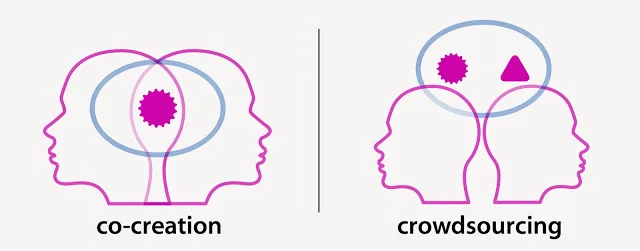

To be clear, there is a vast difference between participating in this crowdsourcing naming contest than merely voting for a favourite entry. The former takes a little more cognitive effort (but not that much), and the latter is essentially just a reaction and only requires a click, and it’s almost too easy.

100,000 is certainly a large and persuasive voting bloc, but 100,000 name suggestions are just overwhelming and unnecessary. The more “name-ideas” you get, the greater the chance they will cover the gamut from the soberly serious to the incredibly silly. The point for the contest designers was to get just enough people involved to garner some media coverage, and they got more than they bargained for.

Perhaps asking the crowd to provide a rationale for their name suggestion or why they voted for a particular name may have tempered the response and reduced the volume. But this would undoubtedly invite more of the same type of non-sensical entries but with different dimensions: From a heartfelt “this is why I think this is a good name ” to the simple-minded “ why not”? Naming things is incredibly subjective, and with no constructive way of measuring the effectiveness of one name or another, you’ll get as many opinions about what makes a great name as you have names.

So what’s the problem with asking the crowd for name ideas? It’s not what you ask; it’s how you ask it. Crowdsourcing a name for a boat seems like a democratic move to be inclusive. But without some serious guideposts, you’ll get responses that will be all over the map.

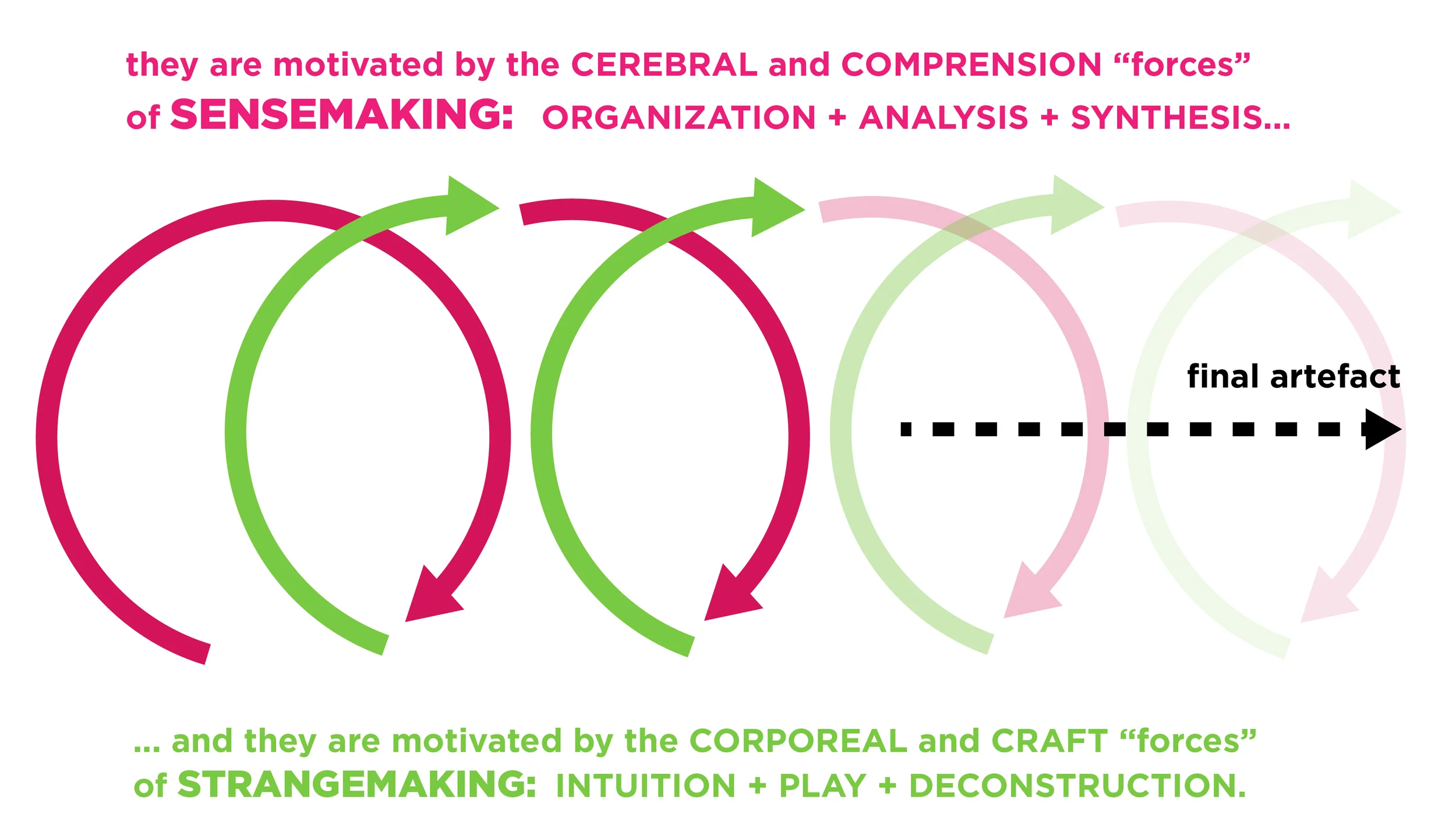

What motivates a crowd to participate?

Why do people participate in crowdsourced challenges in the first place?*

Love of problem-solving

Love of learning new things

Desire to make positive changes

It's all about the prize

Within this framework, it becomes evident that naming contests don't have a lot to offer in return for the time and effort spent to participate. The problem to be solved is one-dimensional. Is it even a problem? And there's not much to learn. What a thing is named hardly matters in any socially meaningful way (it's just a boat), although you might learn a little about the organization.

It's not really about creative problem-solving. Also, the "problem owners" gave themselves an out – which is tantamount to saying we'll go along with the crowd's choice only if we like it... It's no wonder Boaty McBoatface was voted as the favourite.

Inviting the global village to help solve challenges may sound like the most democratic thing you can do. It's an open invitation to all interested in the subject matter at hand to participate. Although this is not a new way of finding the best ideas amongst a crowd**, access to these challenges has been supercharged by the advent of internet technology. It's easier to learn about the challenges, find like-minded collaborators, and conduct research to get all the information you need to inform your solution. The caveat for the authors of any challenge is to address the critical crowd motivators. If your challenge can't match any of these, your contest will likely run aground.

At the very least, the Natural Environment Research Council got more publicity than they ever imagined. Many more people are now aware of who they are and what they do and that they just spent 283 million of public money on a boat. What's the lesson here? There are several.

Crowdsourcing Tips

1. The authors of a challenge need to be highly Transparent (contest rules aside).

Please don't ask the crowd for their input and then ignore them. In the boat naming contests, the contest-authors did make it known that they have a right to veto the crowd's choice. But to have to rely on this backdoor escape hatch will sour the crowd's mood.

2. Naming contests for serious endeavours don't fare well under the weight of a large crowd.

People will game the system, and although there's not much to gain – your name gets to go on an obscure ocean-going vessel, poking fun at the true intent of the contest is the next best thing.

You must make the contest challenge if you want the crowds to help and expect them to put their best foot forward. If you ask the crowd an easy question, you'll always get Boaty McBoatface as your answer.

*Lanier, Jaron. You are not a gadget: A manifesto. Vintage, 2010.

** https://www.crowdsource.com/blog/2013/08/the-long-history-of-crowdsourcing-and-why-youre-just-now-hearing-about-it/